……

‘neath the green Estrella trees

No

Artist merely but a MAN

Wrought

on our noblest island-plan

Sleeps

with the alien Portuguese

Austin Dobson: From verses read at the unveiling, by the

United States Minister, the Hon. Mr. J.

Russell. Lowell, of the Bust of Henry Fielding by the Sculptor Miss Margaret

Thomas in the Shire Hall Taunton.

Austin

Dobson had it wrong, Henry Fielding does not sleep with the alien Portuguese.

They, católicos to a man, would not

be caught dead in the Cemitério dos

Ingleses on the Avenida de Álvares Cabral, a heathen burial ground reserved

for protestantes, judeus,

agnósticos and atheists. He

shares his final resting place mainly with his fellow countrymen and a

smattering of Germans, Dutch and other northern Europeans. He was born in 1707 in Somerset and grew up

in Dorset but he was one of London’s greatest citizens and the fact that he died

and was buried in Lisbon does not stop him being one of the London Dead. I had wanted to pay my respects at his

memorial for some time, something that should have been relatively

straightforward as I regularly visit Lisbon. But somehow whenever I resolved to

make the trip to the cemetery something went wrong; I missed buses, got caught

in downpours of monsoon like ferocity on the streets of Lisbon, turned up in

the afternoon when the cemetery was closed, or lost my way in a tangle of side

streets and alleyways. This year I was

determined to make sure there would be no mishaps and as soon as I was off the

first easyjet flight of the day from Luton airport and out of customs I hailed

a cab and had them take me straight to the cemetery.

Walter

Scott called Fielding the father of the English Novel (an honorific Defoe and

Richardson might both have taken issue with) and Edward Gibbon said that Tom Jones “will outlive the palace of

the Escurial, and the imperial eagle of the house of Austria” (the second part

of his prediction has already been true for the best part of a century though

the Escorial still stands firm). On the other hand Dr Johnson took Hannah Moore

to task when she quoted from some “witty passage” in Tom Jones and expressed his shock “to hear you quote from so

vicious a book. I am sorry to hear you have read it; a confession which no

modest lady should ever make. I scarcely know a more corrupt work." He also called Fielding a blockhead, and when Boswell

demurred furiously elaborated “what I mean by his being a blockhead is that he

was a barren rascal!"

"Will

you not allow, Sir, that he draws very natural pictures of human life?"

Boswell mildly countered.

"Why,

Sir, it is of very low life,” Johnson thundered, ”Richardson used to say, that

had he not known who Fielding was, he should have believed he was an ostler.

Sir, there is more knowledge of the heart in one letter of Richardson's, than

in all Tom Jones.” Coleridge didn’t agree with either Johnson’s

love of Richardson or his disdain for Fielding “What a master of composition

Fielding was! Upon my word, I think the Oedipus

Tyrannus, the Alchemist, and Tom Jones, the three most perfect plots

ever planned. And how charming, how wholesome, Fielding always is! To take him

up after Richardson, is like emerging from a sick room heated by stoves, into

an open lawn.”

Leaving

aside his literary achievements (he wrote for the stage as well as fathering

the novel) Fielding is best known for his job as a Bow Street magistrate. In

this capacity he was notable for his objections to public executions (the

public nature of them being the cause of his opposition rather than the execution

itself, which, like congress with serving girls, he had no particular issue

with as long as it was decently carried out in private), his role in the

formation of the Bow Street runners (in the early days, a wholly inadequate

force of 6 which has multiplied, over the intervening two a half centuries to

32,000 with apparently little effect on the crime rate), his incorruptibility

(in terms of monetary bribes) and his nepotism in job sharing his job over his

blind half brother John.

|

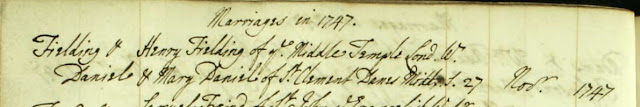

| The marriage registry at St Benet Paul's Wharf showing Fielding's second marriage to Mary Daniels |

Fielding’s

first marriage, in 1734, was to Charlotte Craddock at their local church in

Somerset. It would have been a completely happy marriage if four of the couples

five children had not adopted the habit of dying in infancy and Charlotte, no

doubt heart sore and broken willed, chosen to follow them at a relatively early

age. There is no reason to doubt that

Fielding’s grief was both genuine and profound despite his seeking solace in

the bed of Mary Daniel, his wife’s lady’s maid (who since the death of her

mistress probably didn’t have much else to do).

The liaison was presumably satisfactory in every respect because

Fielding decided to make Mary his second wife. They married on November 27,

1747 at the church of St Benet Paul’s Wharf. According to the 1904 DNB “their

first child was christened three months afterwards. Lady Louisa Stuart reports

that the second wife had been the maid of the first wife. She had ‘few personal

charms,’ but had been strongly attached to her mistress, and had sympathised

with Fielding's sorrow at her loss. He told his friends that he could not find

a better mother for his children or nurse for himself.” Fielding did not share

the view that his wife lacked personal charms; during the next five years she

fell pregnant every year, only her husband’s ill health finally putting an end

to the begetting of further Fielding offspring.

|

| Hogarth's unflattering portrait of Fielding |

By

1752 failing health and premature middle age forced Fielding to resign his

position as magistrate and retire to Ealing where the gout and dropsy

undermined his constitution so badly that by the summer of 1754 newspapers were

reporting his death and then having to print hasty retractions; the Derby

Mercury of the 21st June for example “we have the Pleasure to assure the

Publick, that the Report of the Death of Henry Fielding, Esq; inserted in an

Evening Paper of Thursday, is not true, that Gentleman's Health being better than it has been for some Months

past.” Fielding was not put out by

rumours of his demise; he was in such a poor physical state that he himself

commented that “my face contained marks of a most diseased state, if not of

death itself. Indeed, so ghastly was my countenance that timorous women with

child had abstained from my house, for fear of the ill consequences of looking

at me.” Knowing that if he did nothing the rumours could well become true he

decided to leave Ealing and move south to a sunnier climate. He originally

hankered after Aix-en-Provence but as gout had left him unable to walk and made

carriage rides agony he cast around for someone reachable by ship and settled

on Lisbon.

On

the 3rd August the Oxford Journal reported that “a few Days since Henry

Fielding, Esq; and his Family embark'd for Lisbon, in order to use the Baths

for the Recovery of his Health; and not for the South of France, as mentioned

in some of the Papers.” Fielding had

been trying to leave for Lisbon since June 26, the day he left Ealing on an excruciating

two hour coach ride to join his ship, The Queen of Portugal, at Redriffe

(Rotherhithe). On his own admission he “presented a spectacle of the highest

horror. The total loss of limbs was apparent to all who saw me, and my face

contained marks of a most diseased state, if not of death itself….. In this

condition I ran the gauntlet (so I think I may justly call it) through rows of

sailors and watermen, few of whom failed of paying their compliments to me by

all manner of insults and jests on my misery.” For the five or six weeks

Captain Richard Veale piloted his ship at an agonisingly slow pace down the

Thames, into the estuary and then round the south coast, always hugging the

coastline and waiting for a decent breeze to fill his sails. Fielding passed

his time writing a diary that was published posthumously as ‘The Journal of a

Voyage to Lisbon.’ Fielding may have been dying but he did his best to keep up

his spirits and produce the sort of good humoured, rollicking prose in which he

had written Tom Jones. He failed. Unsurprisingly he struggled to

make light of incidents such as having to call a doctor to drain his stomach of

ten quarts of dropsical fluid.

Fielding

portrays Captain Veale as something of a martinet, a man very prone to standing

upon his dignity. Not brutal, as many ships officers were in those days, but

certainly unyielding and a little harsh except when it came to the ship’s cats.

The dying Fielding wasn’t without a certain degree of sympathy himself when a

kitten fell overboard:

A most tragical

incident fell out this day at sea. While the ship was under sail, but making as

will appear no great way, a kitten, one of four of the feline inhabitants of

the cabin, fell from the window into the water: an alarm was immediately given

to the captain, who was then upon deck, and received it with the utmost concern

and many bitter oaths. He immediately gave orders to the steersman in favour of

the poor thing, as he called it; the sails were instantly slackened, and all

hands, as the phrase is, employed to recover the poor animal. I was, I own,

extremely surprised at all this; less indeed at the captain's extreme

tenderness than at his conceiving any possibility of success; for if puss had

had nine thousand instead of nine lives, I concluded they had been all lost.

The boatswain, however, had more sanguine hopes, for, having stripped himself

of his jacket, breeches, and shirt, he leaped boldly into the water, and to my

great astonishment in a few minutes returned to the ship, bearing the

motionless animal in his mouth. Nor was this, I observed, a matter of such

great difficulty as it appeared to my ignorance, and possibly may seem to that

of my fresh-water reader. The kitten was now exposed to air and sun on the

deck, where its life, of which it retained no symptoms, was despaired of by

all.

But

the cat lived, for the moment, “to the great joy of the good captain, but to

the great disappointment of some of the sailors, who asserted that the drowning

of a cat was the very surest way of raising a favourable wind.” Having survived

a dunk in the ocean the cat that “could not be drowned was found suffocated

under a feather-bed in the cabin. I will not endeavor to describe [Captain

Veale’s] lamentations … than barely by saying they were grievous, and seemed to

have some mixture of the Irish howl in them.”

|

| Lisbon cats proving cemeteries are much safer places than ships for the average feline |

The

Queen of Portugal finally docked at Lisbon at the beginning of August

1754. Approaching Lisbon on the river

Tagus Fielding thought that it looked “very beautiful at a distance”; but was

quickly disillusioned “as you approach nearer… all idea of beauty vanishes at

once.” Soon he was calling it the “nastiest city in the world”. The blistering

heat of August did nothing to mend the writers ailing constitution, just the

opposite in fact, he was soon feeling worse than ever. Within two months he was

dead, though the contrary British press, once keen to record his premature

demise, perversely reported him as returning to full health under the

Portuguese sun. On the 22nd October the Leeds Intelligencer (now there is an

oxymoron for you) told it’s readers that “Letters by the last Mail from Lisbon

advise, that Henry Fielding, Esq; is surprisingly recovered since his Arrival

in that Climate. His Gout has entirely left him, and his Appetite returned.” He

had actually died on the 8th of October and had been interred in the only

possible burial ground for a protestant foreigner, the English Cemetery. His

death left his wife penniless and she returned to England without arranging for

a headstone or any other grave marker for the great author.

If

Mary Daniel did not make arrangements for a headstone perhaps someone else did.

Early accounts of the grave are conflicting as to whether there was a marker or

not. In 1772 Richard Twist visited the cemetery and wrote that “the great

author of Tom Jones (...) is here interred without even a stone to indicate

that here lies Henry Fielding”, while Nathaniel Wraxall in the same year

claimed to have found a headstone “nearly concealed by weeds and nettles”. Twist also pointed out that the unmarked

state of the grave was a national scandal as foreigners could not believe that

“this [is] how the British honour their best and brightest” while the monied but

otherwise undistinguished Portugal traders

filled the cemetery with “marble monuments with long, pompous,

flattering inscriptions” to themselves and their wives. Some of Fielding’s foreign admirers even

proposed taking action themselves; the French consul Chevalier de Meyrionne started one scheme in

1776 but was recalled to France before it could be completed and Dom Joâo de

Braganza, the uncle of the Portuguese Queen and founder of the Lisbon Academy,

tried to raise a monument with a learned Latin epitaph by the Abbé Correa de

Serra but had to abandon the plan in the face of opposition from the catholic

clergy. It was the British Chaplin, the

Reverend Christopher Neville who in 1830 finally raised the necessary cash from

Fielding’s admirers to raise the large, but rather uninspiringly designed,

monument that now stands over his burial place (or perhaps stands over his

burial place; Wordsworth’s daughter Dora Quillien wrote in 1846 that “the exact

spot where Fielding was buried (…) is not known. His monument (…) is on a spot

selected by guess. The bones it covers may possibly have belonged to an idiot.”) The massive chest tomb surmounted by an urn is

very typical of the early 19th century and is not even enlivened with a

portrait though there is an interminable Latin epitaph which starts ‘‘Henrici

Fielding a Somersetensibus apud Glastoniam oriundi’. By the 1880’s newspapers

were reporting that the tomb was being neglected by the guardians of the

cemetery. The following report from the Pall Mall Gazette was reprinted

verbatim in many provincial newspapers:

THE TOMB OF

FIELDING. It appears that the English cemetery Lisbon is in a state of

disgraceful neglect. Here, as everyone knows, Henry Fielding is buried, and

here, as everyone does not know, cartloads of the bones of British soldiers collected

from the battlefields of the Peninsular War, were deposited after 1810. The

tomb Fielding, so a recent visitor writes to the Times, is entirely overgrown,

and even the inscription is in places obliterated. This is certainly not as it

should be, and if the English residents in Lisbon have not sufficient patriotic

piety to tend Fielding's tomb, it devolves on literary England to see that it

be rescued from its present state of neglect. Might not Mr Robert Buchanan at

once advertise "Sophia" and express his gratitude towards Fielding by

trimming and whitewashing his monument as he has trimmed and whitewashed "Tom

Jones?" It would be a graceful act of expiation. ( 01 December 1886, Dundee Evening Telegraph)

|

| From an articles in THe Sphere, 1907 |

Eighteen

months later the Illustrated London News was disputing these stories and

claiming that the tomb was still the scene of veneration for the famous author:

MARCH 17, 1888

THE PLAYHOUSES A few months ago there was a discussion about the condition

Henry Fielding's grave in the Protestant cemetery at Lisbon. Some officious

person wrote to the papers that it was shamefully neglected; but it all turned

out to be ridiculously untrue,' for the grave is of solid stone— perennius —and

it is surrounded flowering shrubs and mournful cypresses, and the English

ladies who visit Lisbon never fail to scatter roses on the solid sarcophagus

containing all that is left of the author of “Tom Jones” and Joseph

Andrews." Illustrated London News - Saturday 17 March 1888

Certainly

no one can complain these days, the cemetery in general and Fielding’s tomb in particular

are immaculately kept. Make sure you visit if you are ever in Lisbon.

No comments:

Post a Comment