Spitalfields

starts somewhere in the warren of streets between Bishopsgate and Commercial

Street. As soon as you come off the main thoroughfare you start running into

groups of tourists being walked around by tour guides. One of the places you

will often find a group of people being lectured by a guide is at the entrance

to an unnamed service road at the side of White’s Row multi-storey car park.

Groups of travellers from Japan, the States, Germany or even from the English

provinces stand here in rapt attention, only moving to lift their camera

viewfinders up to their eyes and take a shot. They are gripped by this

unprepossessing street because it was once Dorset Street, ‘the worst street in

London’ and there, by the steps to the office block, was Miller’s Court, the

scene of Jack the Ripper’s last and most brutal killing of Mary Jane Kelly on

November 9 1888. Hawksmoor’s Christchurch is just around the corner and Iain

Sinclair writes that the building was a

"magnet to the archetypal murder myth of the late 19th century ...

The whole karmic programme of Whitechapel in 1888 moves around the fixed point

of Christ Church ..." Hmmm.

The

street was originally laid out in 1674 and was known as Datchet Street. The

name was gradually corrupted to Dorset Street and the street became full of

doss houses. By the 1880’s it was estimated that 1200 men slept every night in

the lodging houses of a street that was only 400 feet long. Miller’s Court was

built off an alleyway between Dorset Street and Brushfield Street to the north.

Mary Kelly who worked as a prostitute rented a room in the court which she used

to entertain her clients. She had taken a stout ginger haired man who wore a

bowler hat and carried a can of beer back to the room just before midnight on

the 8th November. By 2.00am she was back out on the streets and asking an

acquaintance to give her sixpence. Whilst he was making his excuses Mary was

approached by a man of ‘Jewish appearance’. She took the man home with her and

was never seen alive again. Her landlord sent his assistant to collect the rent

the following morning and it was the unfortunate rent collector who, getting no

response to his knock on the door, opened the curtains through a broken window

and discovered Kelly’s horribly mutilated corpse. Kelly was the only victim to

be photographed at the scene of her murder – the photograph is grainy, blurred,

faded and obviously Victorian but still harrowing and shocking. You can easily

find it on the net if you want to see it.

Fiona

Rule's "The Worst Street in London" is an excellent account of the

history of Dorset Street if you are interested. The photograph below was taken

in 1902 as an illustration for Jack London's "People of the Abyss", a

classic account of the east end and significant contribution to the east end

myth and shows Dorset Street looking west from Commercial Street. Once one of

the most degraded areas of the capital (“in the shadow of Christ's Church, at

three o'clock in the afternoon, I saw a sight I never wish to see again….”

wrote Jack London in “People of the

Abyss”, appalled at the squalid poverty he witnessed in what was meant to be

the greatest city in the world) now an uber-trendy artists quarter where rich

artists and corporate types who like to live somewhere a little bit edgy blow

vast sums to buy houses and flats in the Georgian weavers houses and where the

local colour is now provided by the local Bangladeshi community down Brick

Lane.

It

may look like it has been there since 1888 at least but I’d be surprised if

Verde & Co have been here for even 20 years. The veneer of age and gentle

dilapidation is all carefully contrived. It is a rather expensive delicatessen

serving the new well heeled residents of Spitalfields and the thousands of

people who work in nearby offices. Just across the road is Spitalfields' market

which has been through a similar face lift and now has restaurants as well as

stalls selling designer clothes, arty crafty bric a brac and so on. (It does

have a good second hand book stall though specialising in old Penguin

paperbacks, most of which are only a couple of quid). Christchurch is at the

end of the street, not looking at all like the axis of evil Iain Sinclair would

have us believe it is.

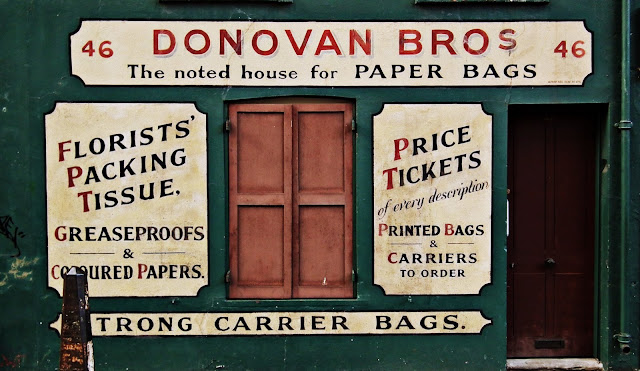

Donovan

Brothers was an authentic east end business at 46 Crispin Street. It was

founded in the 1830’s by Jeremiah and Dennis O’Donovan who came to Spitalfields

from Dublin via Liverpool to escape the economic collapse of Ireland during the

potato famine, and is still going strong, in Leyton rather than Crispin Street

though.

The

foundations for Christ Church were started in the summer of 1714. It took over

14 years and £40,000 to complete the church which was consecrated in July 1729.

Spitalfields lay in the large medieval parish of Stepney which also included

Poplar, Bethnal Green, Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse. In 1710 the Church

Convocation, in its report on parishes that needed new churches, had reported

that Stepney had 86,500 inhabitants, one parish church and two Anglican

chapels-of-ease. In stark comparison the non-conformists had an estimated 19

meeting houses. The church commissioners agreed that the parish needed four new

churches built. All four were eventually built, three were designed by Nicolas

Hawksmoor, Christ Church, St George’s-in-the-East and St Anne’s at Limehouse.

Often

cited as Hawksmoor’s masterpiece but even at the time it was built it was

already out of fashion. The Palladian critic James Ralph wrote, a mere 5 years

after it was consecrated, wrote that the ’monstrous expense’ lavished on it had

resulted in the erection of ’one of the most absurd piles in Europe’. Even in

the 20th century Nicholas Pevsner called it ‘ugly’. Hawksmoor’s original

design, in so far as it can be reconstructed from the extant drawings, did not

include either the Tuscan portico or the gothic looking steeple (see

above).

This piece was originally written and published on Flickr in November/December 2011.

When Gilbert and

George moved into Fournier Street, it was because the monthly rent was £16, and

the landlords didn't mind whether you slept in the building or used it as a

studio. The area was run-down, but, says Gilbert, "totally magic,

romantic". Fournier Street was occupied by buttonmakers, furriers and

hat-makers, and the area was Jewish. "The front doors were open all

day," says George. "All the windows were open, so people would speak

to each other from one side of the street to the other. Extraordinary antique

behaviour."

"This area

has been everything. It's been a Roman cemetery, it's been part of the hospital

for the returning Crusaders. It's been a manufacturing base for guns which,

curiously, was staffed entirely by Germans. "In between the Jews and the

Bangladeshis, it was briefly Maltese, then Somali. It was extraordinary when it

was Maltese because they all had Alsatian dogs, they kept ferrets, they played

cards all day."Their London

centres around Fournier Street, which is now seen as a masterpiece of early

Georgian architecture, just as Gilbert and George are hailed as pioneers of the

East End art scene. "George used to teach in Hoxton in 1967," says

Gilbert. "In the evening, when we came back, my God." "All the

businesses were totally shuttered," says George. "Totally deserted -

scary. You could either have sex with a stranger or get beaten up. Those were

the only two choices. And that was only Hoxton Square!"

"It's

extraordinary to think that within walking distance you can find the tomb of

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism - the tomb of George Fox, the founder of

the Quakers, of Daniel Defoe, author of one of the few books in the world which

is never out of print, John Bunyan, and William Blake," says George.

"Only one grave has a jam-jar of flowers - William Blake". "We

rather like John Bunyan," says Gilbert, "because we feel that's what

we did - Pilgrim's Progress. Every year we have to fight all the moral dilemmas

in ourselves."

To explore this

further, Gilbert and George take me on a tour. The first stop is the mosque on

the corner of Fournier Street and Brick Lane. "That was the synagogue when

we were students," says George. "The posh synagogue at that." "It

was a French church," says Gilbert. "A Huguenot church. They tried to

convert Jewish people to Christianity. It didn't work."

Alastair McKay, Evening Standard 31 Jan 2007

The

name Spitalfields is a contraction of ‘Hospital Fields’ , the fields being ones

that lay in medieval times to the east of the priory of the New Hospital of St Mary without

Bishopgate which presumably stood just outside the city walls (‘without’ in the

sense of ‘there is a green hill far away without a city wall’). Brick Lane runs from Bethnal Green, down

through Spitalfields and ends almost at Whitechapel Road. It was originally called Whitechapel

Lane and took its current name from the brick and tile works that grew up in

the area to take advantage of the local brick earth deposits. As well as bricks brewing was big business.

The most famous was Truman’s Black Eagle brewery (see picture below). The area has always had a large immigrant

population, Huguenot’s in the 18th Century, the Irish and then Ashkenazi Jews

in the 19th and Bengalis in the 20th.

Today Brick Lane is the heart of Banglatown, the street signs are

written in Sylheti as well as English and every other shop is an Indian

restaurant.

If

you get on a walking tour you’ll be shown the brewery and the railway bridge,

whatever recent street art is worth looking at and someone will point out the

brickwork bas relief high on the façade of the Sheraz Balti House that tells

you that this used to be the Frying Pan public house. It was here is this pub

that 43 year olf Polly Nichols, the first of the rippers victims, spent the

last evening of her life. She left the

pub at 12.30am and tried to get a bed at a lodging house in Thrawl Steet ( the

pub stood at the corner of Thrawl Street and Brick Lane) but was thrown out

when it transpired she didn’t have the necessary four pence needed. She was seen on Whitechapel Road at 2.30 but

an hour later her body was discovered at Bucks Row, a few hundred yards away,

with her throat cut and her abdominal area viciously slashed probably after she

was already dead.

From

Brick Lane I walk down to the Whitechapel Road and make my way to St

George's-in-the-East via Cannon Street Road, crossing the Highway (formerly

known as the Ratcliffe Highway), Commercial Road and Cable Street.

This piece was originally written and published on Flickr in November/December 2011.